When Gardens Are like Gingko Trees

Eight years ago, when I first set eyes on our street, I fell in love with the beautiful houses, grouped in threes on a road lined with Gingko trees. It is set on a lovely hill with a picturesque school nearby and fields for walking our dog just five minutes away. Indeed we felt very privileged, and still do, to have found a place such as this that is still so close to the city. We moved a few weeks later and the kids started their new school, delightfully nestled between larches and green playgrounds, and even classified as a cultural heritage site. Things felt perfect, until…. A strange smell started filling the house. And surrounding the outside of the house. It actually smelled like someone had been sick, and I wondered if the kids were overdoing it on the excitement front. Finally we realised it was the fruits of the Gingko trees. But I wasn’t going to let berries dampen my enthusiasm, however smelly.

Now that we were somewhat settled, it was time to actually meet the neighbours. I had decided that I would not do it the Swiss way (which, from what I had sadly gathered from my previous flats, came down to a shy Gruezi when you happened upon a situation where you could no longer pretend not to see each other. Or, and this was more frequent, the “Waschküchi” (laundry room) encounters. This time I was going to do it my way. I decided to see if the Swiss saying: “Wie mä in Wald rüeft so rüeft es zrugg” (“As you call into the forest, so the forest calls back”) held what it promised. I would behave as I wanted to be and approach my surroundings accordingly, namely with a smile and a friendly chat. And indeed, it seemed to work. Our new neighbours all seemed very happy about my ringing their doorbells and introducing myself. Some of them commented about what a nice idea they thought this was. Our next-door neighbour even invited me in for coffee when she found out I only had instant, “Oh,” she said, “That won’t do at all; I’ll make you a real coffee, come in.” We got to chatting and found that we had some similar interests, including writing, and I thought that things just couldn’t get better.

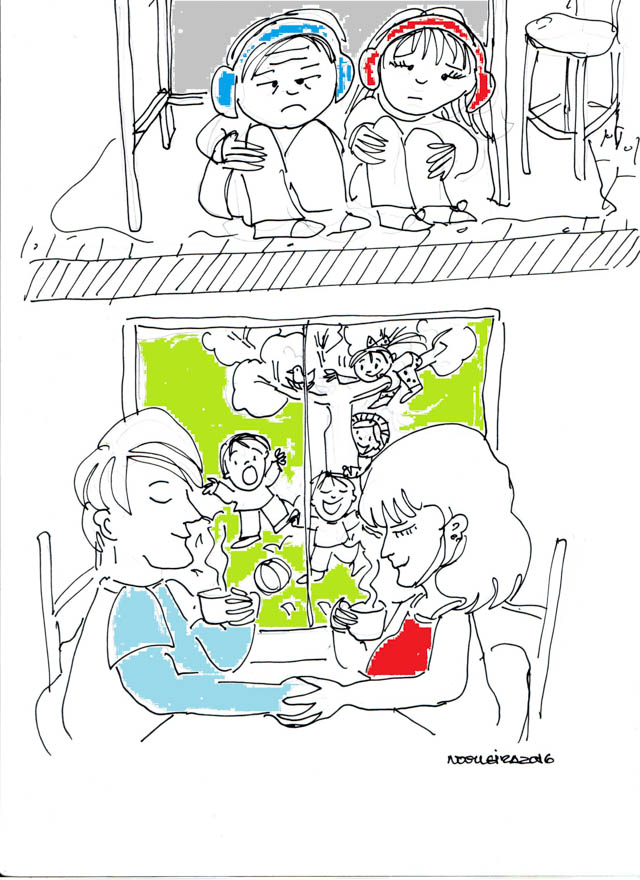

A few days later we invited some friends over. It was a Wednesday afternoon, when all Swiss schoolchildren are generally free, so they brought their kids and we all exploded out into the garden after a frantic run through all the new rooms, up the stairs and down the stairs. The kids were having the time of their lives. The neighbours started playing music turning the volume up loud. I looked at my friend and we gave each other the thumbs up. The kids got some ice cream, while we celebrated with Prosecco.

Then suddenly a voice thundered from behind the fence.

“Ruhe,”

This means “silence.” The word cut off our excitement like a scythe.

It turned out that our new neighbours were about as tolerant of kids and noise as they were of Nescafé.

Then I remembered our first morning, just one week earlier, when my partner and I woke up in our new home and went out onto the veranda for our first cup of coffee. The kids were at my parents’ so it was quiet. Deathly quiet, in fact. We looked at each other. Not a sound. “Did we miss a chemical emergency announcement on the radio?” I wondered out loud.

What sort of a neighbourhood was this? A family neighbourhood where people had gardens but kids weren’t allowed to play in them? I didn’t have time to wonder any further how this was managed, instead I decided after a few sleepless nights of feeling terribly torn, that I wasn’t going to let my kids be bullied like this. I decided to call the police to find out our rights. In fact, they passed me on to a specialist who deals with neighbourly issues. She was amazing and spent the better part of an hour discussing and explaining to me the ins and outs of noise in a Swiss garden. I put down the phone with a smile on my face. Our rights were clear: kids are allowed to be in the garden playing normal games at normal decibel levels (although it could possibly be argued that “normal decibel level” is a matter open to cultural interpretation). Even the occasional kid scream is allowed, and this from the hours between 7:00 until 22:00, with a one-hour lunch break from midday to 13:00. We were sorted, and our life in our new home could begin.

A few weeks later a flyer landed in our post box inviting us to the annual street party. The kids were thrilled to have the entire road free for playing and all day long people seeped out of their houses carrying desserts and salads to the designated tables set out by the street party committee. There was a kids’ circus and later a band came to play. A lively event, it was a lovely chance to get to know each other and, especially for our youngest, a chance to make friends. In fact, since then she meets up with her new friends every morning and they all scoot down to the school together, picking up the others as they pass their houses. And now, seven years later, she is training on her new unicycle so she can join in with the street circus for this year’s street party.

I think it was the street party that then moved parents to initiate a petition for a Spielzone (= play zone), where the children can now use the middle section of the street as an after-school playground. This grand idea has reinforced neighbourly friendships of all generations. (One lady even collected old photographs and stories from the oldest residents who remembered what it was like when they first moved in, and made copies for everyone to see.) It is also a place where noise doesn’t seem to be an issue.

Sometimes, though, I still wonder how exactly they all managed to keep their kids so quiet in their gardens on a normal Wednesday afternoon when the sun was out. And it occurs to me that it’s a little like with the Gingko trees. As long as they appear nice, everyone’s happy, but there’s always the threat of that foul-smelling fruit which can cause unpleasantness and dispute. There is, however, a solution even for that: the Stadtgärtnerei (the Basel city gardeners) are a phone call away, and they do a grand job every year of removing those smelly culprits. The gardens remain remarkably quiet and the noise is out on the street where it belongs. And even though I am tempted every now and then to start an alphorn course just so I could practise in my garden, the nice thing about it is that a solution has been found to cater for everyone’s needs.

By Karin Mohler

Karin has lived between cultures for her entire life and has come to the conclusion that this will always be a big part of her. Having no roots doesn’t bind her anywhere in particular, but she is careful not to impose that sense upon her children, who have been born and bred in Switzerland. She has taken a lot of inspiration for understanding her “in-betweenness” from the book Third Culture Kids: Growing Up among Worlds, by D. C. Pollock and R. V. Reken (2009).

Illustration by Albina Nogueira

Albina Nogueira has been a primary school teacher since 1992, and a writer and illustrator since 2006. She currently lives in Switzerland, but her homeland is Portugal. She is also the author of Letters to Grandparents and Hairdresser. To find out more, like her on Facebook or see her books in Amazon.